small mirror: Helen Mirra

16 Mar—5 May 2023small mirror is Helen Mirra’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. It includes a selection of ‘non-redundant repetitions and benign regressions’, made between 2003 and 2023.

Helen Mirra’s practice has consistently been formally minimal, using simple materials while engaged with maximal ideas about perception and participation as a person on this particular planet. After a number of years making discrete works in various materials, and considering various subjects, her present rhythm is still epitomised in walking.

Every Surface to Come

Cherry Smyth

‘No one uses running water for a mirror.’(1)

Walk backwards. Take care not to fall, or bump into things. The body adjusts, or is it the ground? The feet land and the leg muscles work differently. The back body activates. The skull leans as if to see. What was thought-less becomes very focussed, directing each step. You can no longer read the signs: some other path-finding must come into play. There is no choice but to decelerate. There is no choice.

‘having done something harmless, repeat’(2)

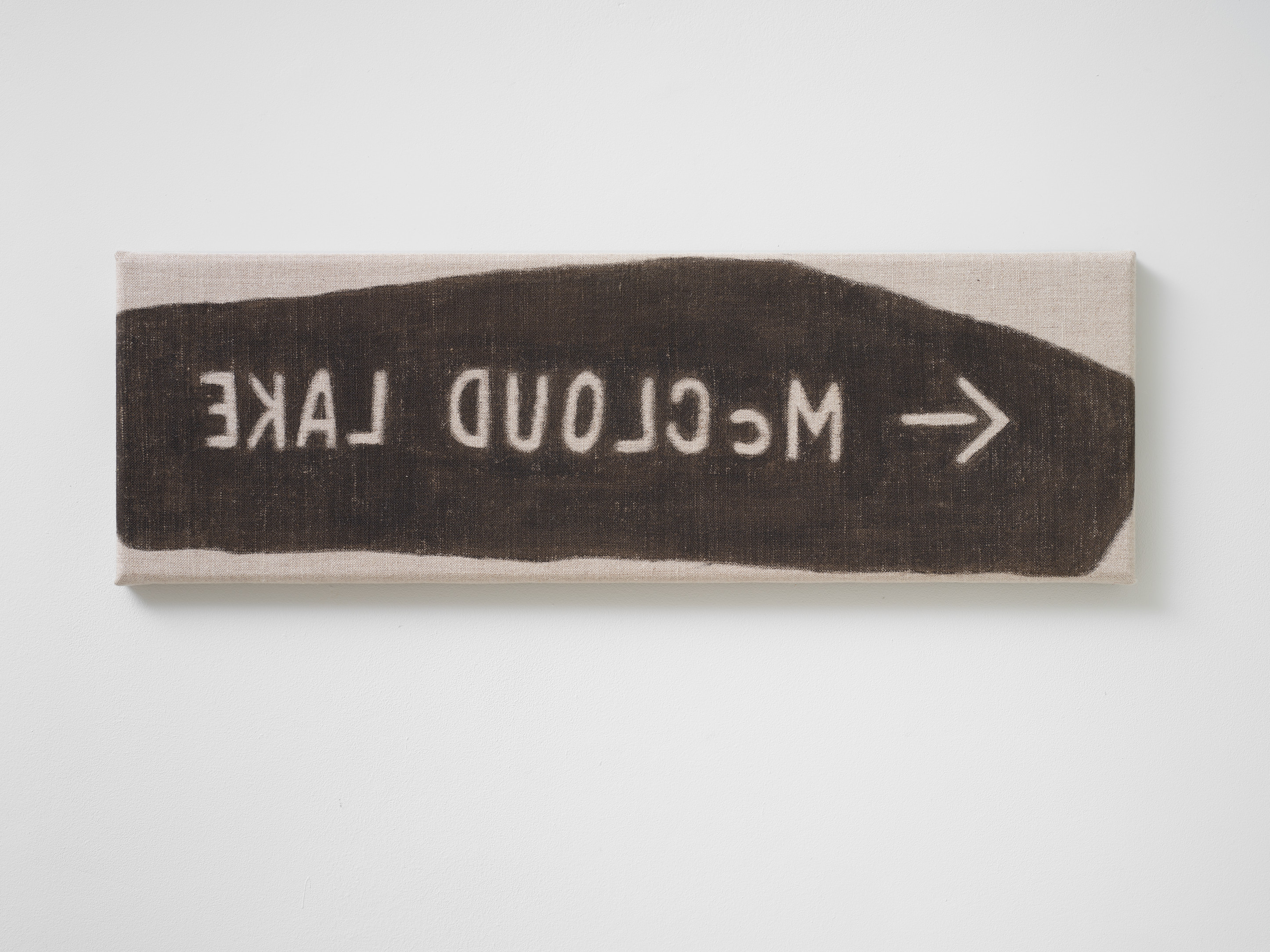

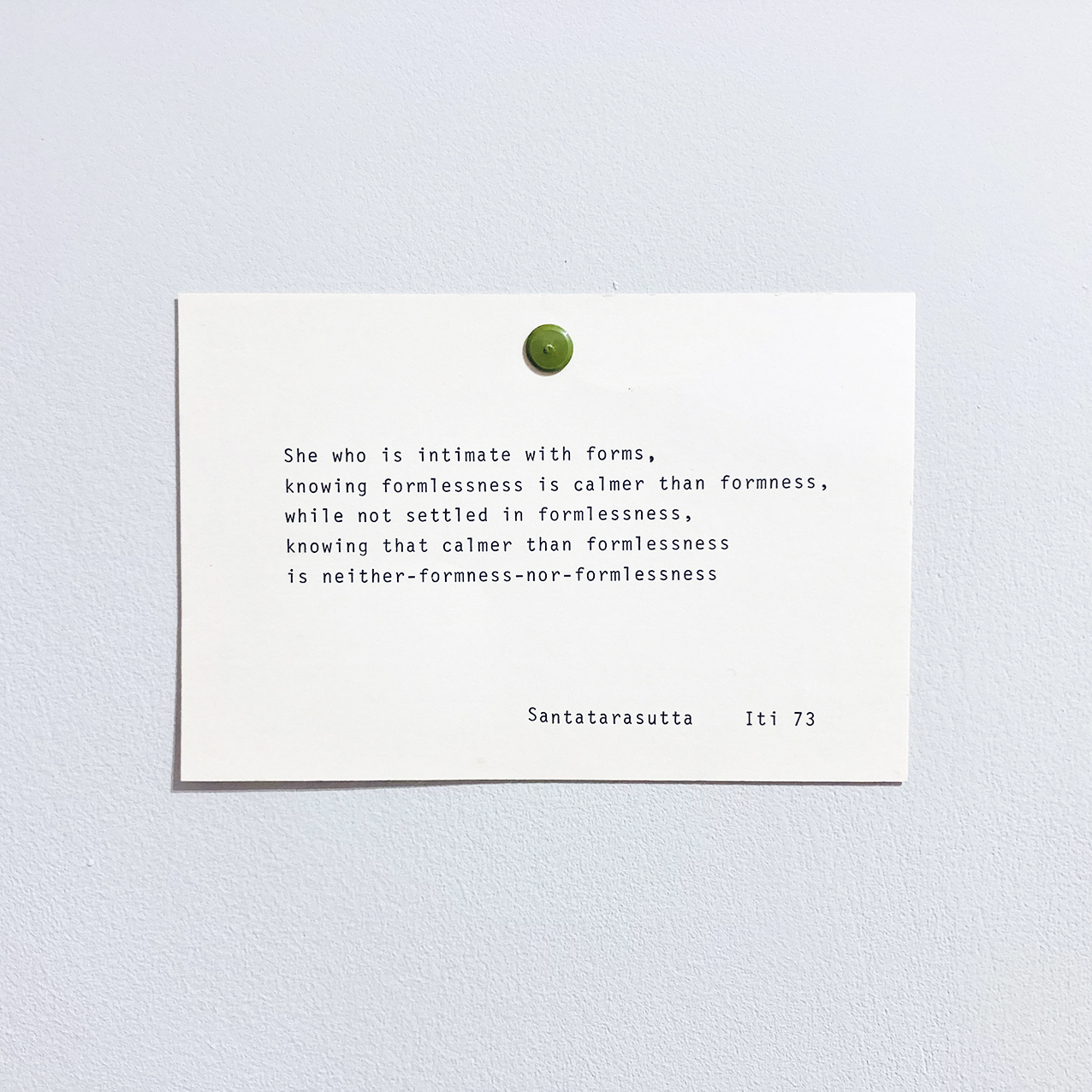

Many of Helen Mirra’s works operate as path-finders that create their own signs. If, as Buddhism attests, ‘where there is a sign, there is deception’, Mirra looks beyond the outer form of things towards signlessness, one of the doors of liberation in every Buddhist tradition. The ink drawings of walking trail signposts in California, are written in mirror writing, as if we are looking from behind the sign, through it. Rather than orientate, they disorientate. If rainbows need rain, is the sign to Rainbow Falls, already a legacy sign? What was its indigenous name? The path was once read in rocks, the slope of mountain, the cast of the sun. The signs pull you in opposing directions: the past of brutally erased names; the future of ongoing, oncoming loss. McCloud Lake is a reservoir, a dammed lake, created for hydroelectric power, trademarked by the ‘Mc’ that conjures Scottish and Irish settlers. If wilderness needs a permit, its status is revoked.

‘delightful are forests unintended for delight’(3)

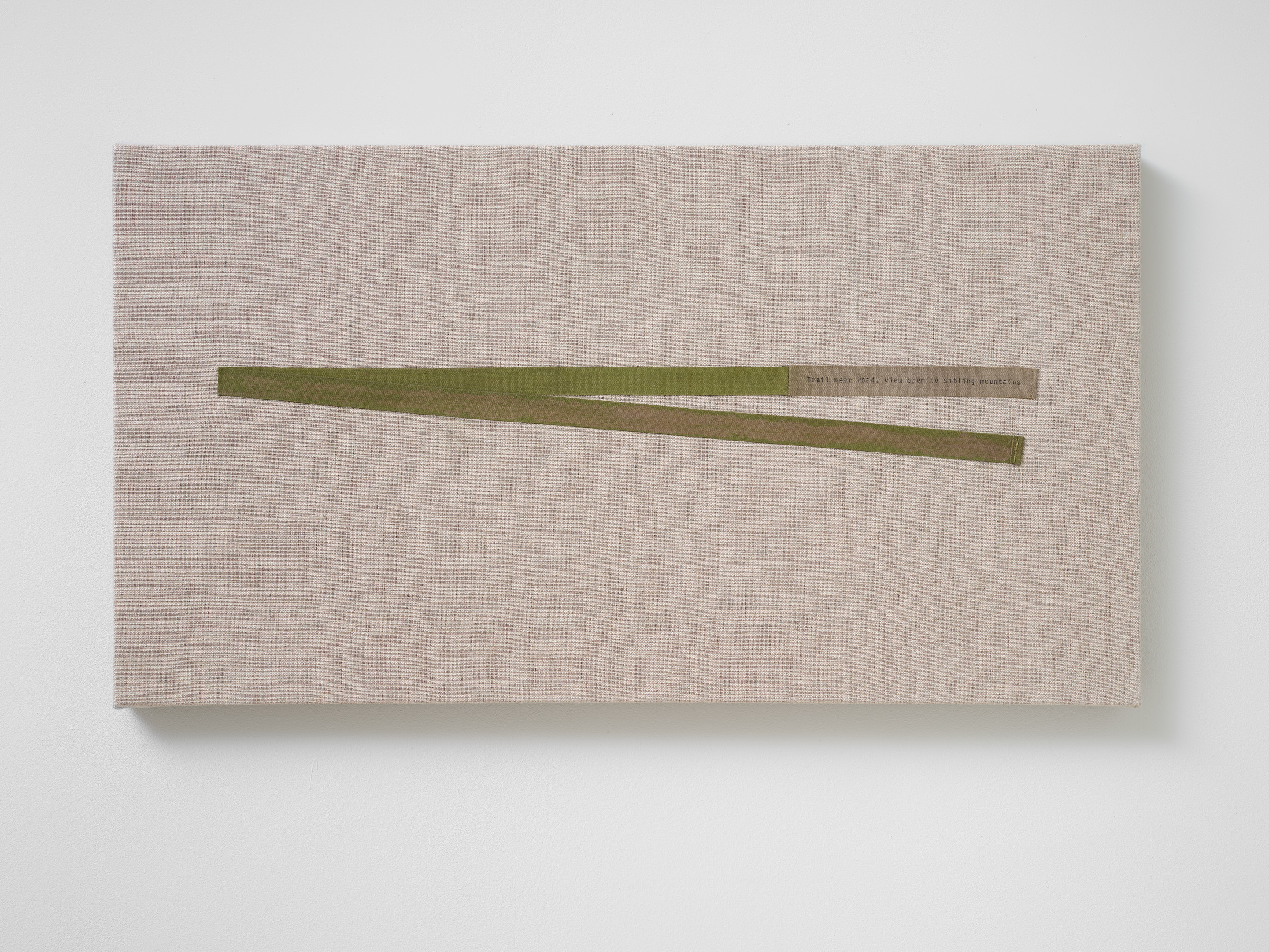

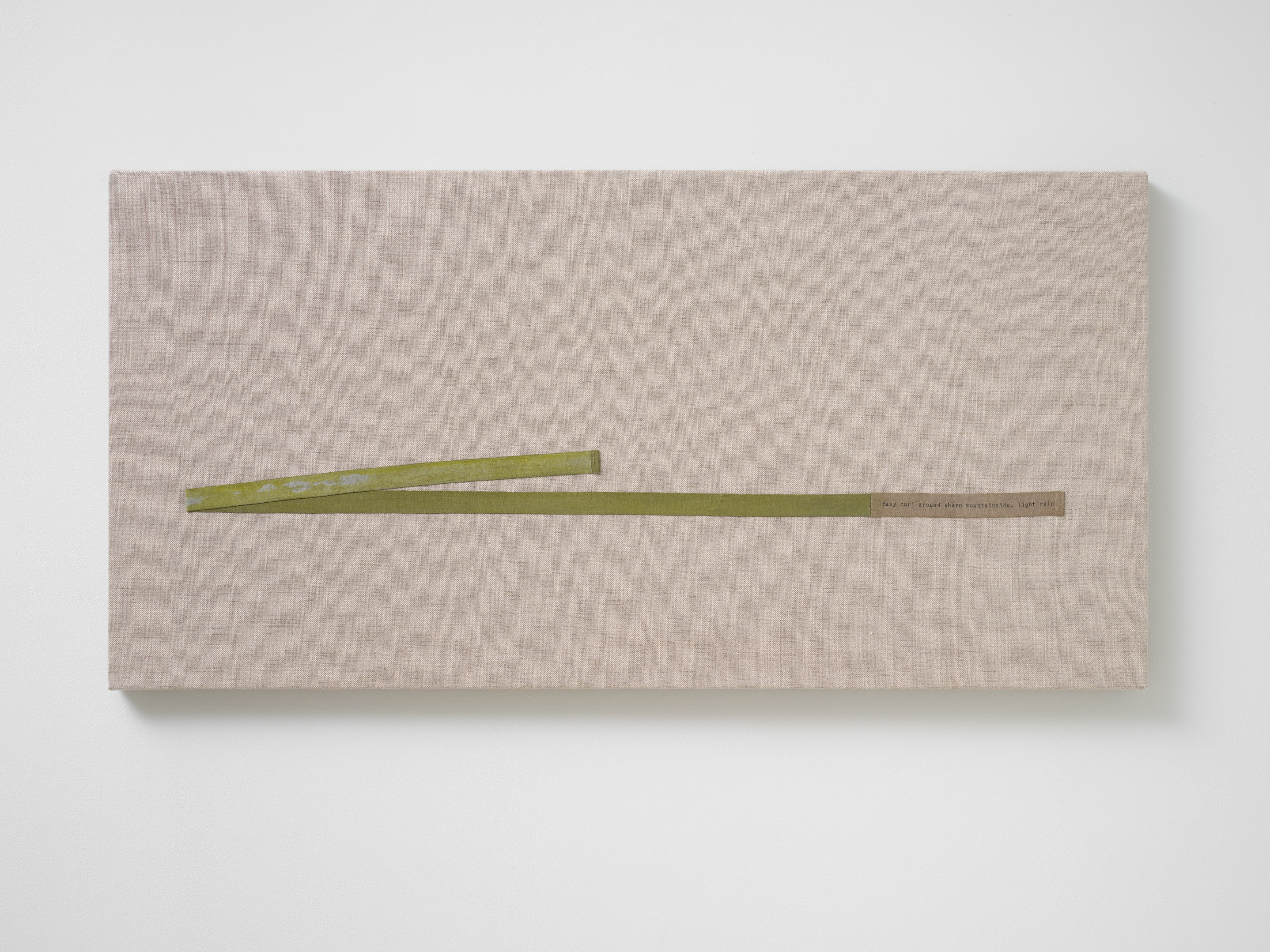

Mirra follows the transient arrows of fallen pine needles. They point from somewhere no one else can go, to a nowhere anyone can go. In their analogue tracking, brief observations are typed on cotton bands, the width of 16mm film stock, hand-painted in ‘colours in the realm of tree-ness.’(4). These beautiful moment maps set up Mirra’s own continuum, a sequence of instances of belonging and letting go.

‘the absence

of a thingin the presence

of its name

curlew’(5)

If the pine needle collages act as loose sentences, Mirra pulls what she calls the art and science of walking into a calendar of text and image in the ‘walking comma’ series. Morning sun picks out a quartz rock, a twiggy ground, marking human time against geological time: a palm holding a rock. These photo/texts form indexes of perception: light bleach, height reached, a pause: sun down behind the mountains, a wrist in a shirtsleeve and sweater.

‘One day it will stop:

the air will stop, the light will stop.’(6)

To baffle is to confound but also to muffle sound.

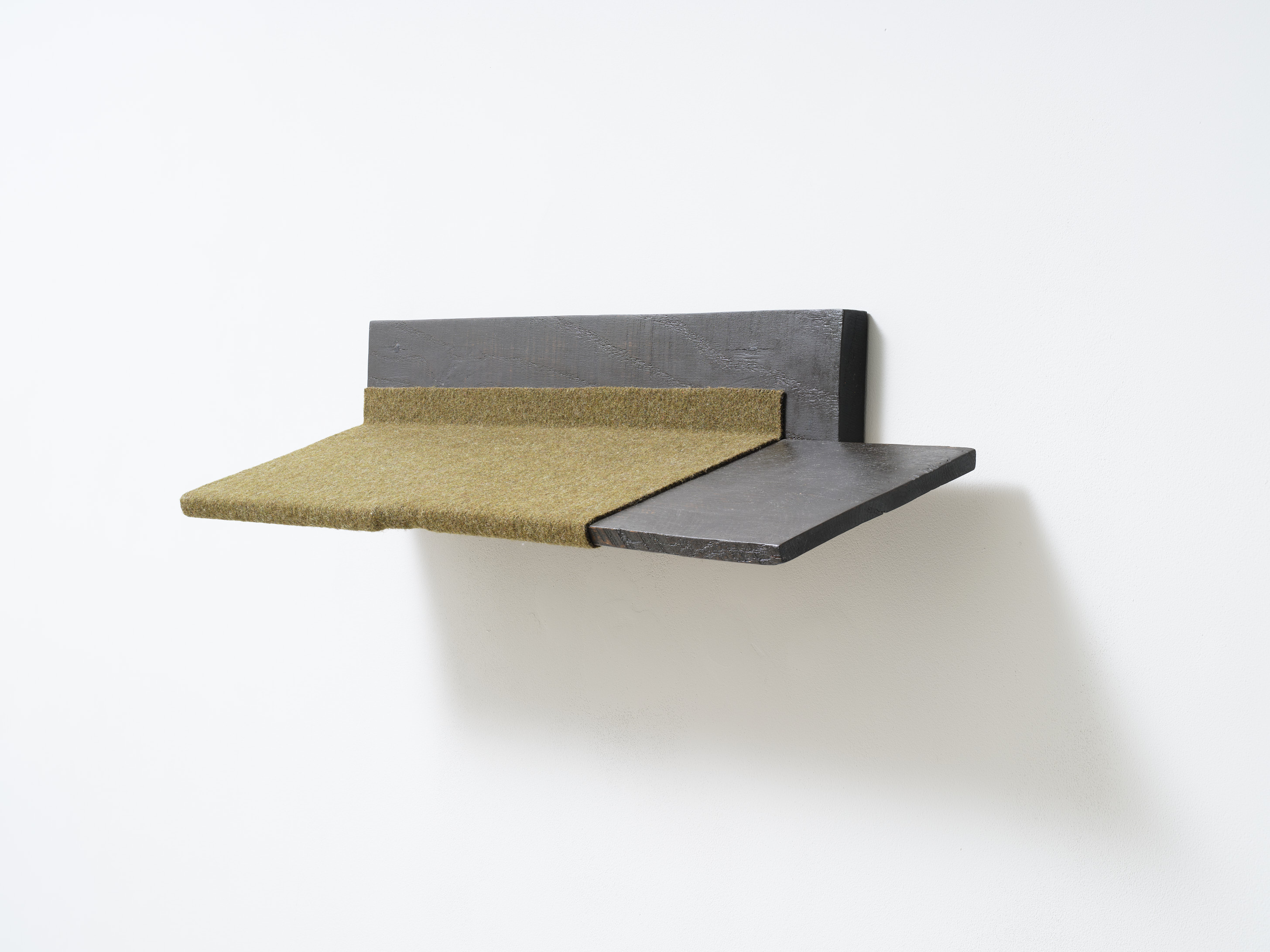

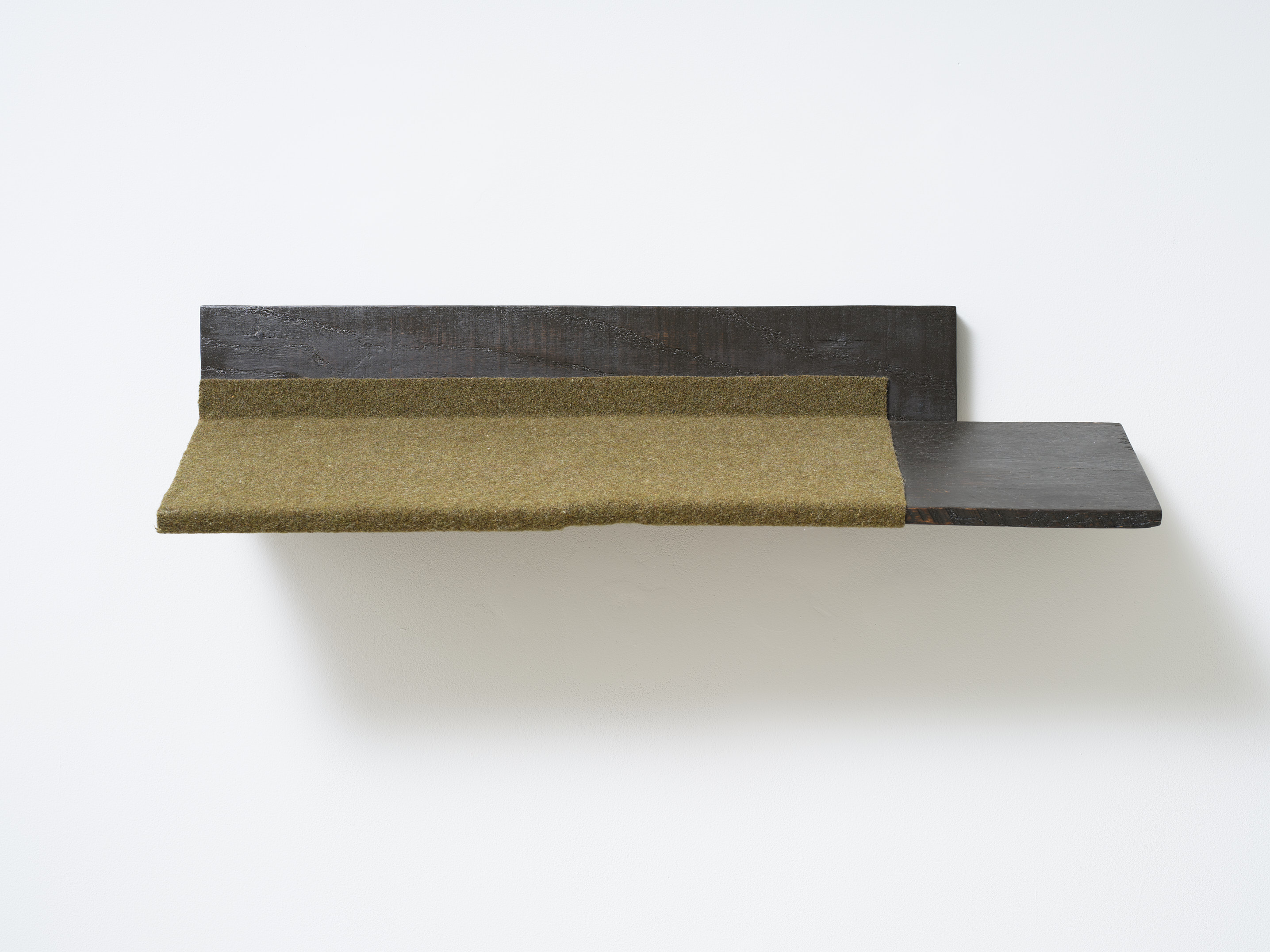

Mirra’s ‘paragrafs’ stand out by their muteness. Their failed shelves hint at functionality, again suggest legacy: an old lacquered desk, a wool cape, the felt pads on the legs of furniture. They exude an air of devotion and care: something precious is wrapped here, felted against cold, against knocks; protected by materials from a time when safe meant it. How far back is that?

Just as ‘para-graphein’ once meant the mark denoting a new section of writing, but came to be applied to the new section itself, so these objects acts as signs that have changed sense. They resemble heirloom holders that have lost their heirlooms. Think of a jeweller’s shop window after closing and all the display units are empty, some shaped in the elegance of a neck and clavicle. Here, ancestors are referenced but unreachable. The index, and its knowledge, closes up on itself.

(1) Confucius, quoted in The Essential Chuang Tzu, ed.& trans. Sam Hammill & J.P. Seaton, Shambala: Boston, 1998

(2) Dp 118, Dhammapada via Fronsdal, 2006, quoted in good nothing, Helen Mirra, Merve Verlag: Leipzig, 2021

(3) Ibid. Dp 99

(4) Helen Mirra quoted in Edge Habitat Materials, White Walls Inc.: Chicago, 2014

(5) Thomas A. Clark, The Threadbare Coat, Carcanet: Manchester, 2020, p.78

(6) Sean Borodale, from ‘Hot Bright, Visionary Flies’, Inmates, Cape: London, 2021

Cherry Smyth is an Irish writer, living in London.

She has published five poetry collections and one novel. She writes regularly for Art Monthly.

Helen Mirra’s practice has consistently been formally minimal, using simple materials while engaged with maximal ideas about perception and participation as a person on this particular planet. After a number of years making discrete works in various materials, and considering various subjects, her present rhythm is still epitomised in walking.

Every Surface to Come

Cherry Smyth

‘No one uses running water for a mirror.’(1)

Walk backwards. Take care not to fall, or bump into things. The body adjusts, or is it the ground? The feet land and the leg muscles work differently. The back body activates. The skull leans as if to see. What was thought-less becomes very focussed, directing each step. You can no longer read the signs: some other path-finding must come into play. There is no choice but to decelerate. There is no choice.

‘having done something harmless, repeat’(2)

Many of Helen Mirra’s works operate as path-finders that create their own signs. If, as Buddhism attests, ‘where there is a sign, there is deception’, Mirra looks beyond the outer form of things towards signlessness, one of the doors of liberation in every Buddhist tradition. The ink drawings of walking trail signposts in California, are written in mirror writing, as if we are looking from behind the sign, through it. Rather than orientate, they disorientate. If rainbows need rain, is the sign to Rainbow Falls, already a legacy sign? What was its indigenous name? The path was once read in rocks, the slope of mountain, the cast of the sun. The signs pull you in opposing directions: the past of brutally erased names; the future of ongoing, oncoming loss. McCloud Lake is a reservoir, a dammed lake, created for hydroelectric power, trademarked by the ‘Mc’ that conjures Scottish and Irish settlers. If wilderness needs a permit, its status is revoked.

‘delightful are forests unintended for delight’(3)

Mirra follows the transient arrows of fallen pine needles. They point from somewhere no one else can go, to a nowhere anyone can go. In their analogue tracking, brief observations are typed on cotton bands, the width of 16mm film stock, hand-painted in ‘colours in the realm of tree-ness.’(4). These beautiful moment maps set up Mirra’s own continuum, a sequence of instances of belonging and letting go.

‘the absence

of a thingin the presence

of its name

curlew’(5)

If the pine needle collages act as loose sentences, Mirra pulls what she calls the art and science of walking into a calendar of text and image in the ‘walking comma’ series. Morning sun picks out a quartz rock, a twiggy ground, marking human time against geological time: a palm holding a rock. These photo/texts form indexes of perception: light bleach, height reached, a pause: sun down behind the mountains, a wrist in a shirtsleeve and sweater.

‘One day it will stop:

the air will stop, the light will stop.’(6)

To baffle is to confound but also to muffle sound.

Mirra’s ‘paragrafs’ stand out by their muteness. Their failed shelves hint at functionality, again suggest legacy: an old lacquered desk, a wool cape, the felt pads on the legs of furniture. They exude an air of devotion and care: something precious is wrapped here, felted against cold, against knocks; protected by materials from a time when safe meant it. How far back is that?

Just as ‘para-graphein’ once meant the mark denoting a new section of writing, but came to be applied to the new section itself, so these objects acts as signs that have changed sense. They resemble heirloom holders that have lost their heirlooms. Think of a jeweller’s shop window after closing and all the display units are empty, some shaped in the elegance of a neck and clavicle. Here, ancestors are referenced but unreachable. The index, and its knowledge, closes up on itself.

(1) Confucius, quoted in The Essential Chuang Tzu, ed.& trans. Sam Hammill & J.P. Seaton, Shambala: Boston, 1998

(2) Dp 118, Dhammapada via Fronsdal, 2006, quoted in good nothing, Helen Mirra, Merve Verlag: Leipzig, 2021

(3) Ibid. Dp 99

(4) Helen Mirra quoted in Edge Habitat Materials, White Walls Inc.: Chicago, 2014

(5) Thomas A. Clark, The Threadbare Coat, Carcanet: Manchester, 2020, p.78

(6) Sean Borodale, from ‘Hot Bright, Visionary Flies’, Inmates, Cape: London, 2021

Cherry Smyth is an Irish writer, living in London.

She has published five poetry collections and one novel. She writes regularly for Art Monthly.

Hendl Helen Mirra

Enquiries

press: Edward Ball

sales: Charlotte Schepke

other: Large Glass

Photos: Stephen White & Co

Enquiries

press: Edward Ball

sales: Charlotte Schepke

other: Large Glass

Photos: Stephen White & Co