John Gossage: From the Garden to the Darkness

14 Mar —30 May 2026“Photography has always seemed to me a place where formality meets reality, or if you would like to say, opinion finds a place in fact.”

We are delighted to present the first exhibition of American artist John Gossage in the UK.

John Gossage (born 1946) is widely regarded as one of the finest American photobook makers of the last 40 years. His first monograph, The Pond (1985), has recently been republished to great acclaim, and is considered a classic by photographers and educators alike. Lisette Model was his teacher. Discovered at a young age by Leo Castelli, one of his first exhibitions was held alongside Jasper Johns. After leaving Castelli, Gossage devoted himself to creating photobooks. In 2015, the Art Institute of Chicago held a major retrospective of his work.

In From the Garden to the Darkness, we focus on two key works which serve as bookends. Gardens is a portfolio of twenty-four photographs with text excerpts selected by Walter Hopps. It was published by The Hollow Press and Castelli Graphics in 1978. The photographs were made between 1973 and 1977 in Washington, DC, where Gossage lives.

The second is from a series of pictures that photograph the darkness in Berlin 1982 - 86. They are the subject of Gossage’s book Stadt des Schwarz (City of Black) and the heart of his later book Berlin in the Time of the Wall.

Positioned between the bookends are what Gossage calls “photographs with distractions”, pieces made from single, small photographs mounted on board with collage-like elements and handmade marks. “I think of them as assemblages. They are not collages because none of the elements intrude upon the photographic reality”, he says in a conversation with Darius Himes.

The images are from There and Gone (1997), a book in three chapters… the first chapter being the bathing beach in the Mexican border city of Tijuana. The pictures were taken from a distance, using a long telephoto lens and surveillance film. John Gossage: “There’s a lot of illegal border crossing and at the same time it’s the beach of the people of Tijuana. What seemed interesting to me was the photographing of strangers. I could go on the beach and do the standard photojournalist pantomime where you spend a couple of days blending in, getting to know the people, but it’s a lie, an illusion. Given this I decided to stay at a distance and photograph people who didn’t know that they were being photographed. All of the pictures taken of Mexico are done from America, about a quarter mile down the beach. I could just stand there and shoot all day, anything that went on, taking another culture on its own terms.”

Gossage’s photographs have been exhibited and are represented in major public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal; the Bibliothèque National, Paris; the Sprengel Museum Hannover, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, among others. Other notable publications include There and Gone; The Things That Animals Care About; The Romance Industry; Berlin in the Time of the Wall; The Thirty-Two Inch Ruler; Looking up Ben James – A Fable, and Should Nature Change.

In 1987, Gossage started his own publishing imprint, Loosestrife Editions, which has published a number of photographic monographs to great acclaim, including A New Map of Italy, Guido Guidi’s first book published outside of Italy.

The exhibition includes an homage to Gossage by Guidi.

We are delighted to present the first exhibition of American artist John Gossage in the UK.

John Gossage (born 1946) is widely regarded as one of the finest American photobook makers of the last 40 years. His first monograph, The Pond (1985), has recently been republished to great acclaim, and is considered a classic by photographers and educators alike. Lisette Model was his teacher. Discovered at a young age by Leo Castelli, one of his first exhibitions was held alongside Jasper Johns. After leaving Castelli, Gossage devoted himself to creating photobooks. In 2015, the Art Institute of Chicago held a major retrospective of his work.

In From the Garden to the Darkness, we focus on two key works which serve as bookends. Gardens is a portfolio of twenty-four photographs with text excerpts selected by Walter Hopps. It was published by The Hollow Press and Castelli Graphics in 1978. The photographs were made between 1973 and 1977 in Washington, DC, where Gossage lives.

The second is from a series of pictures that photograph the darkness in Berlin 1982 - 86. They are the subject of Gossage’s book Stadt des Schwarz (City of Black) and the heart of his later book Berlin in the Time of the Wall.

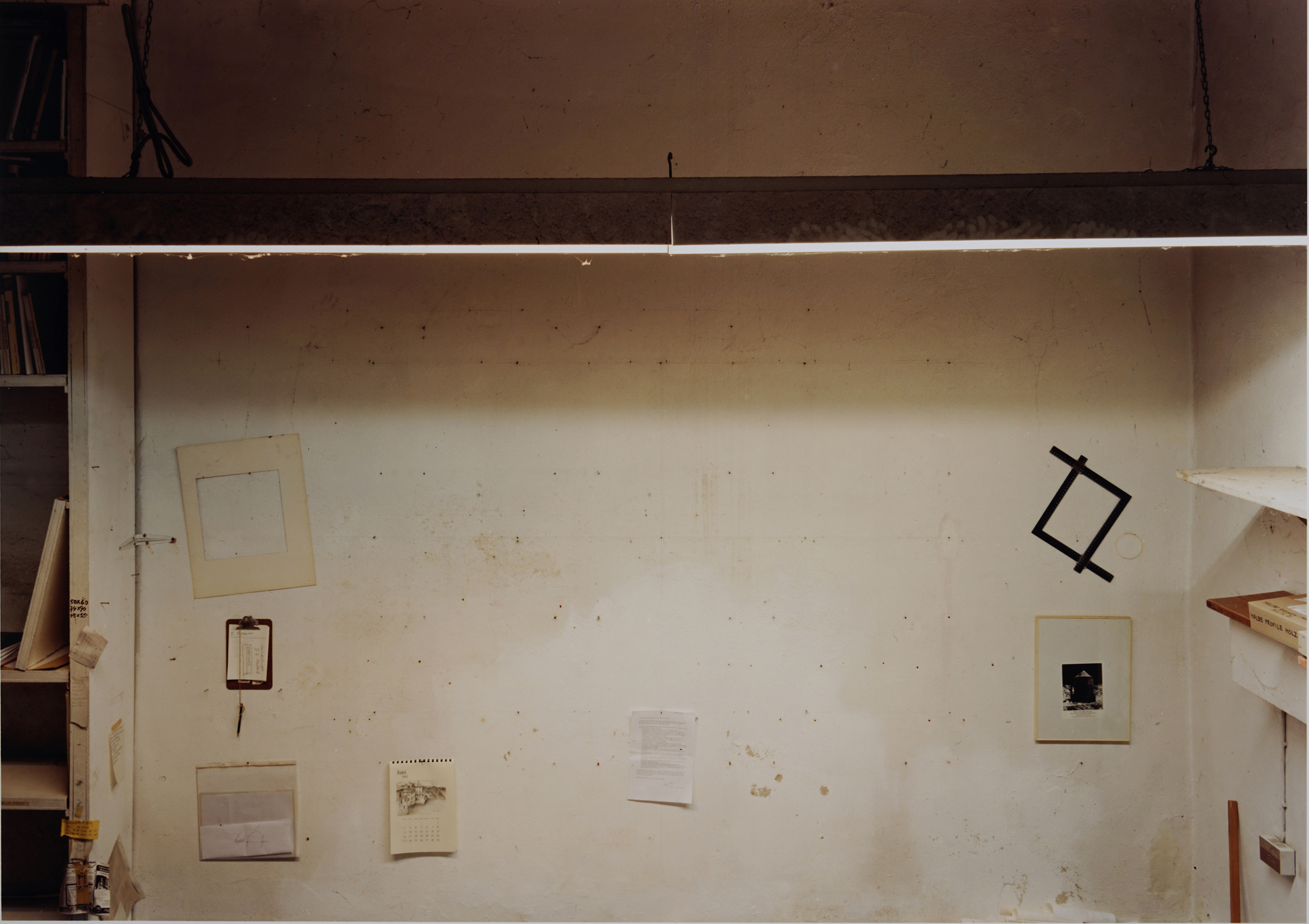

Positioned between the bookends are what Gossage calls “photographs with distractions”, pieces made from single, small photographs mounted on board with collage-like elements and handmade marks. “I think of them as assemblages. They are not collages because none of the elements intrude upon the photographic reality”, he says in a conversation with Darius Himes.

The images are from There and Gone (1997), a book in three chapters… the first chapter being the bathing beach in the Mexican border city of Tijuana. The pictures were taken from a distance, using a long telephoto lens and surveillance film. John Gossage: “There’s a lot of illegal border crossing and at the same time it’s the beach of the people of Tijuana. What seemed interesting to me was the photographing of strangers. I could go on the beach and do the standard photojournalist pantomime where you spend a couple of days blending in, getting to know the people, but it’s a lie, an illusion. Given this I decided to stay at a distance and photograph people who didn’t know that they were being photographed. All of the pictures taken of Mexico are done from America, about a quarter mile down the beach. I could just stand there and shoot all day, anything that went on, taking another culture on its own terms.”

Gossage’s photographs have been exhibited and are represented in major public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal; the Bibliothèque National, Paris; the Sprengel Museum Hannover, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, among others. Other notable publications include There and Gone; The Things That Animals Care About; The Romance Industry; Berlin in the Time of the Wall; The Thirty-Two Inch Ruler; Looking up Ben James – A Fable, and Should Nature Change.

In 1987, Gossage started his own publishing imprint, Loosestrife Editions, which has published a number of photographic monographs to great acclaim, including A New Map of Italy, Guido Guidi’s first book published outside of Italy.

The exhibition includes an homage to Gossage by Guidi.

︎︎︎ ︎︎︎

Guido Guidi: A casa

Guest appearance John Gossage

28 Nov 2025—28 Feb 2026A casa is a collection of work that focuses on the famed Italian photographer's home in Ronta, near Cesena. Purchased by Guidi’s father in the 1950s, this house is both a living space and a studio, as well as a meeting place for emerging artists – a space where personal memories and artistic process intertwine, and where his extensive archive is housed.

Fellow artist and bookmaker John Gossage has been a long time friend of Guidi’s. The two have been on many photographic journeys together and for A casa, he has made a small sequence of six books, acknowledging the gift of friendship, featuring photographs taken on visits to Guidi’s house, a homage to an esteemed artist.

Journalist Bartolomeo Sala travelled to Guido Guidi’s home to ask him about this place, the long time setting for his life as well as his approach to photography. An excerpt of their conversation here:

BS In one of your interviews, I read a sentence of yours that felt particularly revealing, “geography is biography.”

For anyone who grew up around here, your house and the landscape that surrounds it are synonymous with the Padan Plain – the sort of third landscape between urban and rural that you and Ghirri first put on the map in Viaggio in Italia. How much did this landscape have an influence on your sensibility and way of photographing?

GG A lot, it influenced me a lot. If you look at certain things, you train your eye on them, then obviously they become [your subject]. Merleau-Ponty used to say, “if you look at a stone, you become the stone.” If you look at certain rocks, they somehow become part of your mental make-up, so you are drawn to observe them again. If you live somewhere else – say, Milan – maybe, there are stones there, too. But there are mostly shop windows, so you spend your days shooting shop windows. You are yourself a shop window, you have digested it and made it your own, so to speak.

Guido Guidi (b. 1941, Cesena) is one of Italy’s most respected photographers, with a career spanning more than five decades. He has mostly focused his lens on rural and suburban geographies close to his home. Guidi has produced over 30 monographs to date, including the recently published ‘Col tempo, 1956–2024’ (MACK), accompanying a comprehensive retrospective currently touring Europe, from the MAXXI, Rome to LE BAL, Paris. Guidi’s photographs are part of International public collections, including the Victoria and AlbertMuseum, London; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Centre Pompidou, Paris; Fondazione SandrettoRe Rebaudengo, Turin and ICCD in Rome; Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal and San FranciscoMuseum of Modern Art.

John Gossage (b. 1946, Staten Island, New York, USA) lives and works in Washington, D.C. Gossage is known for his nuanced studies of urban and peripheral landscapes. Since the 1960s, his work has examined the interplay between architecture, memory, and social space, often through sequences of black-and-white photographs. Gossage’s publications, including The Pond (1985) and Berlin in the Time of the Wall (2004), are regarded as seminal contributions to the photobook form. His work is held in major collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Bartolomeo Sala is an Italian journalist and editor based in London. His writing has appeared in the Financia Times Weekend Magazine, the Sunday Times, and The New Statesman and he is a regular contributor to Jacobin, and the Brooklyn Rail.

Fellow artist and bookmaker John Gossage has been a long time friend of Guidi’s. The two have been on many photographic journeys together and for A casa, he has made a small sequence of six books, acknowledging the gift of friendship, featuring photographs taken on visits to Guidi’s house, a homage to an esteemed artist.

Journalist Bartolomeo Sala travelled to Guido Guidi’s home to ask him about this place, the long time setting for his life as well as his approach to photography. An excerpt of their conversation here:

BS In one of your interviews, I read a sentence of yours that felt particularly revealing, “geography is biography.”

For anyone who grew up around here, your house and the landscape that surrounds it are synonymous with the Padan Plain – the sort of third landscape between urban and rural that you and Ghirri first put on the map in Viaggio in Italia. How much did this landscape have an influence on your sensibility and way of photographing?

GG A lot, it influenced me a lot. If you look at certain things, you train your eye on them, then obviously they become [your subject]. Merleau-Ponty used to say, “if you look at a stone, you become the stone.” If you look at certain rocks, they somehow become part of your mental make-up, so you are drawn to observe them again. If you live somewhere else – say, Milan – maybe, there are stones there, too. But there are mostly shop windows, so you spend your days shooting shop windows. You are yourself a shop window, you have digested it and made it your own, so to speak.

Guido Guidi (b. 1941, Cesena) is one of Italy’s most respected photographers, with a career spanning more than five decades. He has mostly focused his lens on rural and suburban geographies close to his home. Guidi has produced over 30 monographs to date, including the recently published ‘Col tempo, 1956–2024’ (MACK), accompanying a comprehensive retrospective currently touring Europe, from the MAXXI, Rome to LE BAL, Paris. Guidi’s photographs are part of International public collections, including the Victoria and AlbertMuseum, London; Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Centre Pompidou, Paris; Fondazione SandrettoRe Rebaudengo, Turin and ICCD in Rome; Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal and San FranciscoMuseum of Modern Art.

John Gossage (b. 1946, Staten Island, New York, USA) lives and works in Washington, D.C. Gossage is known for his nuanced studies of urban and peripheral landscapes. Since the 1960s, his work has examined the interplay between architecture, memory, and social space, often through sequences of black-and-white photographs. Gossage’s publications, including The Pond (1985) and Berlin in the Time of the Wall (2004), are regarded as seminal contributions to the photobook form. His work is held in major collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Bartolomeo Sala is an Italian journalist and editor based in London. His writing has appeared in the Financia Times Weekend Magazine, the Sunday Times, and The New Statesman and he is a regular contributor to Jacobin, and the Brooklyn Rail.

Guido Guidi

John Gossage

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Press

Tide Magazine: ‘”A Casa", Guido Guidi at His Home Studio in Ronta’, 19 February 2026

Exhibition Text

‘Guido Guidi: A casa’ featuring an interview with Guido Guidi by Bartolomeo Sala, November 2025

John Gossage

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Press

Tide Magazine: ‘”A Casa", Guido Guidi at His Home Studio in Ronta’, 19 February 2026

Exhibition Text

‘Guido Guidi: A casa’ featuring an interview with Guido Guidi by Bartolomeo Sala, November 2025

︎︎︎ ︎︎︎

Paris Photo 2025 Main Sector, Booth B28

13–16 November 2025Preview Day 12 November (invitation only)

Grand Palais

3 avenue du Général Eisenhower

75008 Paris

www.parisphoto.com

Large Glass (London) and Matèria (Rome) are pleased to announce their joint participation in the 2025 edition of Paris Photo. They will be presenting a shared booth, B28, in the main sector of the fair.

The two galleries are dedicating a focused display of works by the acclaimed Italian artist, Mario Cresci. Both galleries share in representation and commitment to Cresci's exceptional work.

“Cresci is regarded as one of photography’s great experimental artists, writes Josh Lustig in the Financial Times. His work is seeped in the traditions of architecture, design and anthropology, as much as it is in photography. With all of his work, so disparate stylistically, there are multiple conversations taking place. Not only between histories of visual representation, but also between peoples and cultures.”

Alongside this presentation Large Glass will present works by Guido Guidi, Mark Ruwedel and Gerry Johansson. Matèria gallery will present works by Sunil Gupta.

The two galleries are dedicating a focused display of works by the acclaimed Italian artist, Mario Cresci. Both galleries share in representation and commitment to Cresci's exceptional work.

“Cresci is regarded as one of photography’s great experimental artists, writes Josh Lustig in the Financial Times. His work is seeped in the traditions of architecture, design and anthropology, as much as it is in photography. With all of his work, so disparate stylistically, there are multiple conversations taking place. Not only between histories of visual representation, but also between peoples and cultures.”

Alongside this presentation Large Glass will present works by Guido Guidi, Mark Ruwedel and Gerry Johansson. Matèria gallery will present works by Sunil Gupta.

Mario Cresci, Guido Guidi, Gerry Johansson, Mark Ruwedel

Enquiries

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

sales: Charlotte Schepke

Enquiries

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

sales: Charlotte Schepke

︎︎︎ ︎︎︎

Light Industry

19 Sep—15 Nov 2025Light Industry brings together the work of nine artists and photographers, across generations who have worked within the theme of industry. Each of them has focused their lens on human interaction with machines or large tools, industrial areas and their architecture, building sites or labor itself and the traces of these in post-industrial landscapes from the US to Russia, to Sweden, Italy, England and Wales. Viewed collectively, "Light Industry" explores how industries, past and present, and of various scales and levels of visibility, continue to impact our bodies and shape the wider environment.

Caught between excessive expansion and disappearance through decline or deliberate obscuration, the mundane, lived reality of industry in this moment, seems to have fallen out of focus or been temporarily lost from view. In turning to the overlooked and forgotten traces of industry, "Light Industry" brings our relationship to different modes of production back into focus. In doing so, it asks us to reacquaint ourselves, both with the people on whose hard labor industry depends but also with the tactile sensibility and physicality of materials whether found in industrial architecture, post-industrial landscapes or on the surfaces of a print. (from the text by Lucy Rogers)

For a period of two weeks, the exhibition extends outside the gallery to two large billboards across the Caledonian Road, next to the railway bridge, with artwork by Rut Blees Luxemburg and Morgan Levy.

Laurenz Berges (b. 1966, Cloppenburg, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. Berges' photographic work focuses primarily on transience, and the space between use and decay. Berges studied under Bernd Becher and spent a year assisting Evelyn Hofer in the 1980’s. Selected Exhibitions: The Becher House in Mudersbach, The Photographic Collection SK Kultur, Cologne (solo, 2023/24); Josef Albers Museum Quadrat, Bottrop (solo, 2020).

Guido Guidi (b. 1941, Cesena, Italy) lives and works in Cesena. Guido Guidi is one of Italy’s most respected photographers, with a career spanning more than five decades. He has mostly focused his lens on rural and suburban geographies close to his home. Selected Exhibitions: ‘Col tempo, 1956–2024’, a comprehensive retrospective is currently touring Europe from the MAXXI, Rome, and is accompanied by a major new monograph published by MACK.

Craigie Horsfield (b. 1949, Cambridge, UK) lives and works in London. Horsfield’s work combines film, photography, sound, engraving and drawing, and is most well-known for his large-scale, unique prints. He often prints the photographs many years after they were first taken, bringing into contrast memory and the present reality. Selected Exhibitions: Documenta X and XI, Kassel (group 1997, 2002); Tate Britain, London (solo, 2017). He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1996.

Gerry Johansson (b. 1945, Örebro, Sweden) lives and works in Höganäs. Johansson is one of Sweden’s most renowned photographers. Working mostly in black and white, and favouring the square format, Johansson is attracted to the neglected details of urban space. Selected Exhibitions: Les Rencontres de la Photographie, Arles (group, 2024); Moderna Museet, Stockholm (solo, 1982 and 2003). He has been awarded the Prince Eugen Medal for outstanding artistic achievement in 2024.

Morgan Levy (b. 1985, Philadelphia, USA) based in Brooklyn. Levy combines performance, staged photography and documentary approaches, often working in partnership with her collaborators. Levy is informed by canonical 20th century images of work and labour in America, and feminist photographic practices from the 1970s onwards. Selected Exhibitions: V&A Parasol Foundation Prize for Women in Photography, Peckham24 (group, 2025).

Rut Blees Luxemburg (b. 1967, Germany) based in London. Blees Luxemburg is Professor of Urban Aesthetics at the Royal College of Art. She re-envisions cities through large-scale photographic works, public art installations, and operatic productions. Selected Exhibitions: Werkstatt Fotografie, Hamburg (group, 2024); Museum of London, London (solo, 2015).

Roger Palmer (b. 1946, Portsmouth, UK) lives and works in Glasgow. Working as an artist and educator since the 1970s, Palmer's research and practice have contributed to debates on the representation of place, as well as ideas of location and dislocation, migration and settlement. Selected Exhibitions: Centre of Contemporary Art, Glasgow (solo, 2022); South African National Gallery, Cape Town (group, 2000).

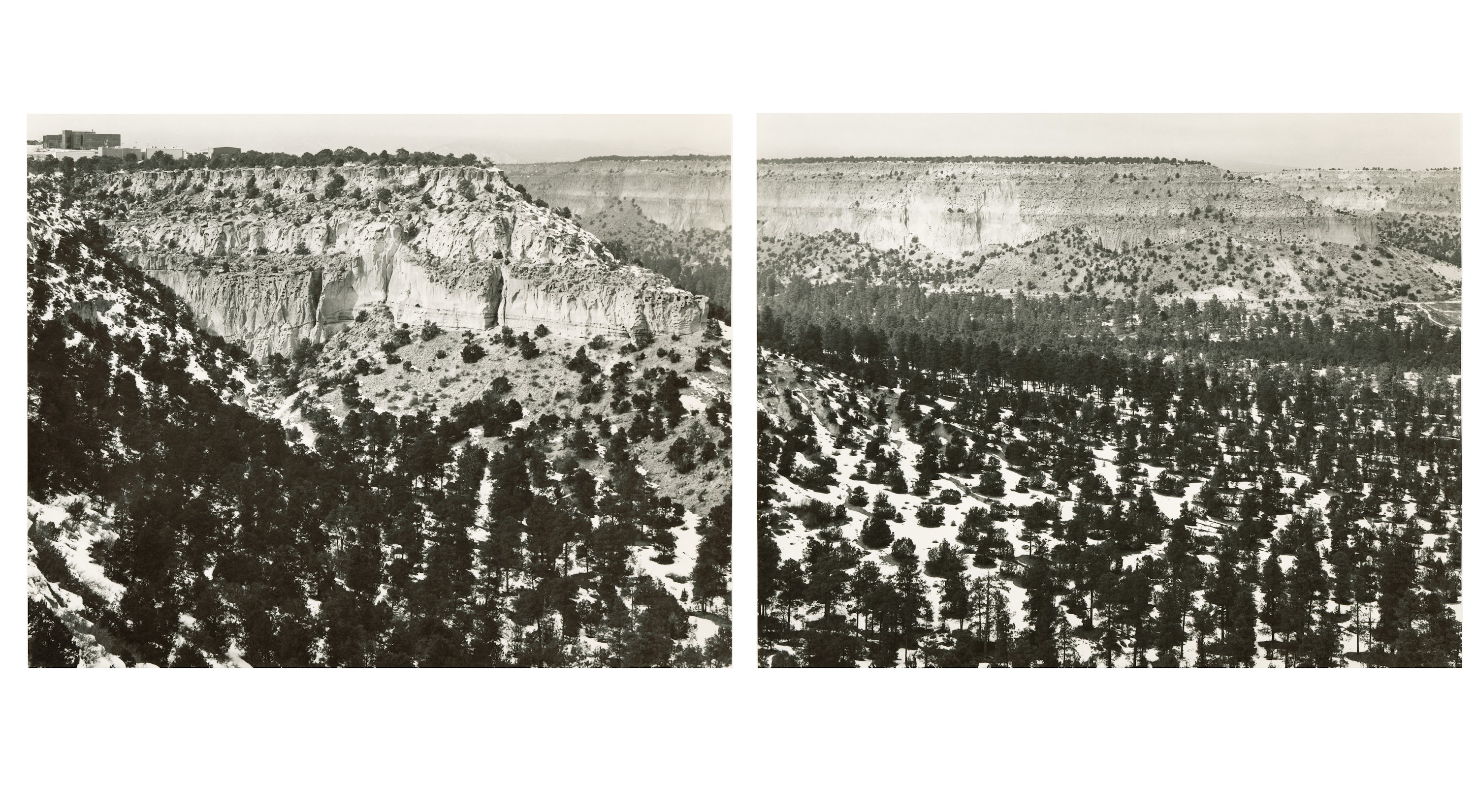

Mark Ruwedel (b. 1954, Bethlehem, USA) lives in Los Angeles. Working primarily in the western territories of the US and Canada, Ruwedel's work explores how geological, historical and political events leave their marks on the landscape. Merging documentary and conceptual methods, he also finds influence in land art echoed in his images of abandoned railways, nuclear testing sites and empty desert homes. Selected Exhibitions: Tate Modern, London, (solo, 2018); Getty Museum, Los Angeles, (group, 2019). He was awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Scotiabank Photography Award in 2014.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg (b. 1938, Berlin, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg grew up in the aftermath of the Second World War. Since the 1970s, she has sought out places of transit and borderlands, locations geographically and politically caught up in a state of in-between. Selected Exhibitions: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, (solo, 2025); MEP, Paris, (solo, 2019/20) Tate Modern, London, (solo, 2013). Schulz-Dornburg has been awarded both the NRW Art Award and the Bernd and Hilla Becher Award in 2025.

Lucy Rogers (text) is an artist, writer and researcher. She has just completed her PhD on the archive of the photographer, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and has curated the exhibition, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: Memoryscapes at Large Glass gallery in 2023.

Caught between excessive expansion and disappearance through decline or deliberate obscuration, the mundane, lived reality of industry in this moment, seems to have fallen out of focus or been temporarily lost from view. In turning to the overlooked and forgotten traces of industry, "Light Industry" brings our relationship to different modes of production back into focus. In doing so, it asks us to reacquaint ourselves, both with the people on whose hard labor industry depends but also with the tactile sensibility and physicality of materials whether found in industrial architecture, post-industrial landscapes or on the surfaces of a print. (from the text by Lucy Rogers)

For a period of two weeks, the exhibition extends outside the gallery to two large billboards across the Caledonian Road, next to the railway bridge, with artwork by Rut Blees Luxemburg and Morgan Levy.

Laurenz Berges (b. 1966, Cloppenburg, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. Berges' photographic work focuses primarily on transience, and the space between use and decay. Berges studied under Bernd Becher and spent a year assisting Evelyn Hofer in the 1980’s. Selected Exhibitions: The Becher House in Mudersbach, The Photographic Collection SK Kultur, Cologne (solo, 2023/24); Josef Albers Museum Quadrat, Bottrop (solo, 2020).

Guido Guidi (b. 1941, Cesena, Italy) lives and works in Cesena. Guido Guidi is one of Italy’s most respected photographers, with a career spanning more than five decades. He has mostly focused his lens on rural and suburban geographies close to his home. Selected Exhibitions: ‘Col tempo, 1956–2024’, a comprehensive retrospective is currently touring Europe from the MAXXI, Rome, and is accompanied by a major new monograph published by MACK.

Craigie Horsfield (b. 1949, Cambridge, UK) lives and works in London. Horsfield’s work combines film, photography, sound, engraving and drawing, and is most well-known for his large-scale, unique prints. He often prints the photographs many years after they were first taken, bringing into contrast memory and the present reality. Selected Exhibitions: Documenta X and XI, Kassel (group 1997, 2002); Tate Britain, London (solo, 2017). He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1996.

Gerry Johansson (b. 1945, Örebro, Sweden) lives and works in Höganäs. Johansson is one of Sweden’s most renowned photographers. Working mostly in black and white, and favouring the square format, Johansson is attracted to the neglected details of urban space. Selected Exhibitions: Les Rencontres de la Photographie, Arles (group, 2024); Moderna Museet, Stockholm (solo, 1982 and 2003). He has been awarded the Prince Eugen Medal for outstanding artistic achievement in 2024.

Morgan Levy (b. 1985, Philadelphia, USA) based in Brooklyn. Levy combines performance, staged photography and documentary approaches, often working in partnership with her collaborators. Levy is informed by canonical 20th century images of work and labour in America, and feminist photographic practices from the 1970s onwards. Selected Exhibitions: V&A Parasol Foundation Prize for Women in Photography, Peckham24 (group, 2025).

Rut Blees Luxemburg (b. 1967, Germany) based in London. Blees Luxemburg is Professor of Urban Aesthetics at the Royal College of Art. She re-envisions cities through large-scale photographic works, public art installations, and operatic productions. Selected Exhibitions: Werkstatt Fotografie, Hamburg (group, 2024); Museum of London, London (solo, 2015).

Roger Palmer (b. 1946, Portsmouth, UK) lives and works in Glasgow. Working as an artist and educator since the 1970s, Palmer's research and practice have contributed to debates on the representation of place, as well as ideas of location and dislocation, migration and settlement. Selected Exhibitions: Centre of Contemporary Art, Glasgow (solo, 2022); South African National Gallery, Cape Town (group, 2000).

Mark Ruwedel (b. 1954, Bethlehem, USA) lives in Los Angeles. Working primarily in the western territories of the US and Canada, Ruwedel's work explores how geological, historical and political events leave their marks on the landscape. Merging documentary and conceptual methods, he also finds influence in land art echoed in his images of abandoned railways, nuclear testing sites and empty desert homes. Selected Exhibitions: Tate Modern, London, (solo, 2018); Getty Museum, Los Angeles, (group, 2019). He was awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Scotiabank Photography Award in 2014.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg (b. 1938, Berlin, Germany) lives and works in Düsseldorf. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg grew up in the aftermath of the Second World War. Since the 1970s, she has sought out places of transit and borderlands, locations geographically and politically caught up in a state of in-between. Selected Exhibitions: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, (solo, 2025); MEP, Paris, (solo, 2019/20) Tate Modern, London, (solo, 2013). Schulz-Dornburg has been awarded both the NRW Art Award and the Bernd and Hilla Becher Award in 2025.

Lucy Rogers (text) is an artist, writer and researcher. She has just completed her PhD on the archive of the photographer, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and has curated the exhibition, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: Memoryscapes at Large Glass gallery in 2023.

Laurenz Berges

Guido Guidi

Craigie Horsfield

Gerry Johansson

Morgan Levy

Rut Blees Luxemburg

Roger Palmer

Mark Ruwedel

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Exhibition Text

‘Light Industry’, Lucy Rogers, September 2025

Guido Guidi

Craigie Horsfield

Gerry Johansson

Morgan Levy

Rut Blees Luxemburg

Roger Palmer

Mark Ruwedel

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Exhibition Text

‘Light Industry’, Lucy Rogers, September 2025

︎︎︎ ︎︎︎

The Edge of Forever

Emma McNally, Alison Turnbull

13 Jun—6 Sep 2025The Edge of Forever is an exhibition of paintings by Alison Turnbull and drawings by Emma McNally. The title is borrowed from the planetary scientist Carl Sagan’s 1980’s book Cosmos.

"Enmeshed in infinities, artists and scientists conjure with the universe from within the confines of the human body, under the deadlines imposed by a limited lifespan.", writes Dava Sobel (author of Longitude) in her accompanying text. "They apply mathematics and imagination. They detect tremors emanating from collisions between the most massive dying stars. They hear the music of the spheres."

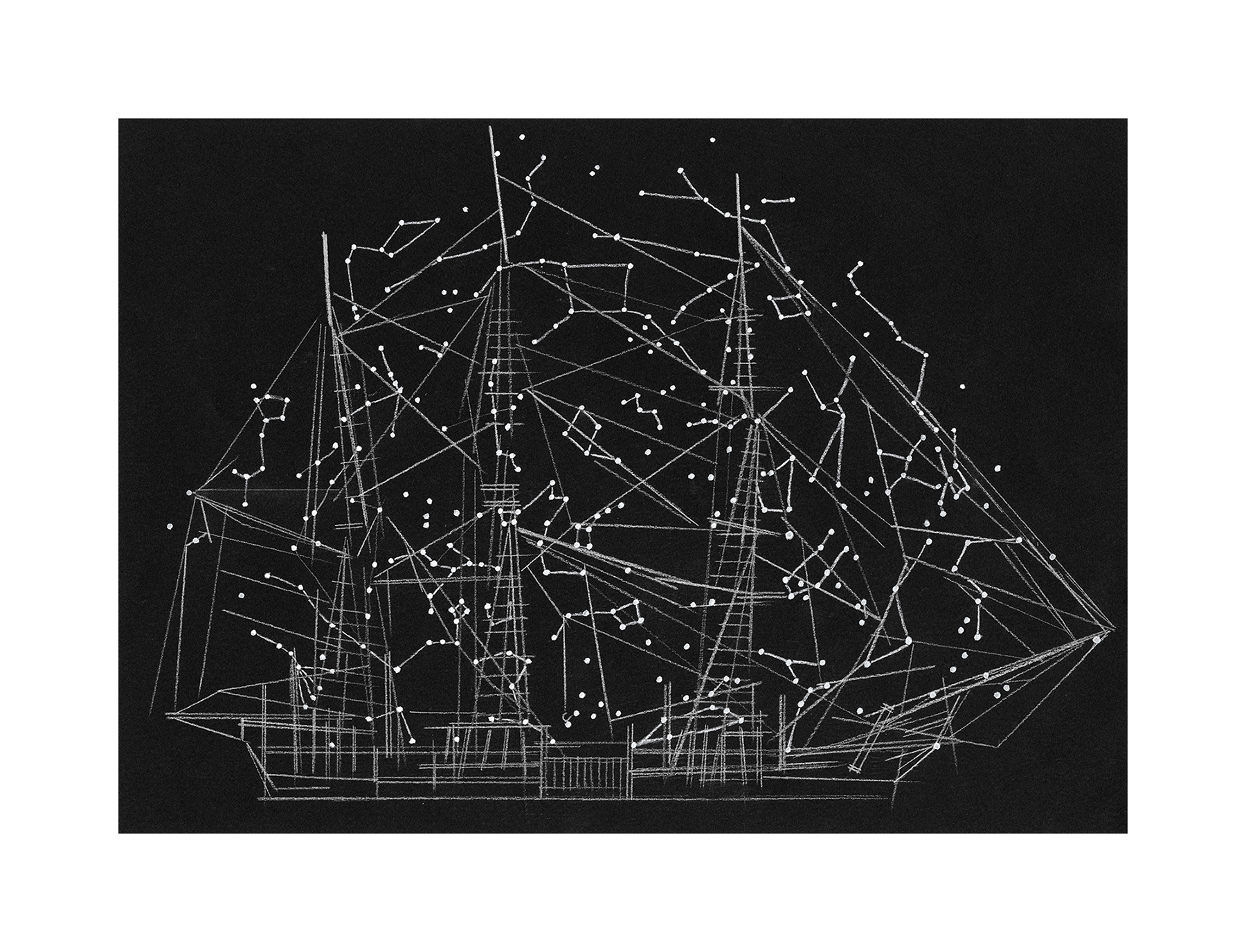

Emma McNally’s meticulous drawings suggest maps or charts of things as complex and various as seas, the night sky, military bases, computer circuit boards, flight paths. "For me drawing is a rhythmic material sounding of inseparability. ‘Song X’ series is staying with the trouble of the edge, the border: an attempt at a dynamic reformulation. Maybe forever (always, all ways) abides in the scrambling of the idea of the edge, which is to say, in borderlessness, inseparability, indeterminacy, entanglement, rhythm, deep field."

Alison Turnbull's expansive painting series 'eXtreme Deep Field' derives from a composite astronomical image made using the Hubble Space Telescope, eXtreme Deep Field. For Turnbull the Hubble image, has a strong relationship with painting: "It’s a picture of time that is very densely constructed; if you looked out through a telescope you would never actually see this, and it moves photography far beyond the question of analogue or digital… Here the notion of the 'onement' of painting is set against the infinity of the image."

Emma McNally (b. 1969, Essex) lives and works in London. McNally studied Philosophy and Literature at the University of York before continuing her thinking visually through drawing. Recent group and solo exhibitions include: The Drawing Room, London, UK (2024); ‘Afterness’, Artangel / National Trust, Orford Ness, UK (2021); 20th Biennale of Sydney, AU (2016) and ‘The form of the Form’; Lisbon Architecture Triennale (2016); ‘Mirrorcity’, Hayward Gallery, London, UK (2015); ‘Seeing/Knowing’, Kenyon College of Liberal Arts, Ohio, US (2011).

Alison Turnbull, (b. 1956, Bogotá, Colombia) lives and works in London. Turnbull transforms readymade information – plans, diagrams, blueprints, charts – into abstract paintings. Selected solo and group exhibitions include Casas Riegner, Bogotá (2025); Inverleith House, Edinburgh (2022); Many Minute Attentions, co-curated by Alison Turnbull and John Stezaker, Large Glass (2021); Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (2021); Saicoro, Tokyo (2020); Matt’s Gallery, London (2018); Five Easy Pieces, Large Glass, London; (2017); Turner Contemporary, Margate (2016); De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill (2014); Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (2012).

"Enmeshed in infinities, artists and scientists conjure with the universe from within the confines of the human body, under the deadlines imposed by a limited lifespan.", writes Dava Sobel (author of Longitude) in her accompanying text. "They apply mathematics and imagination. They detect tremors emanating from collisions between the most massive dying stars. They hear the music of the spheres."

Emma McNally’s meticulous drawings suggest maps or charts of things as complex and various as seas, the night sky, military bases, computer circuit boards, flight paths. "For me drawing is a rhythmic material sounding of inseparability. ‘Song X’ series is staying with the trouble of the edge, the border: an attempt at a dynamic reformulation. Maybe forever (always, all ways) abides in the scrambling of the idea of the edge, which is to say, in borderlessness, inseparability, indeterminacy, entanglement, rhythm, deep field."

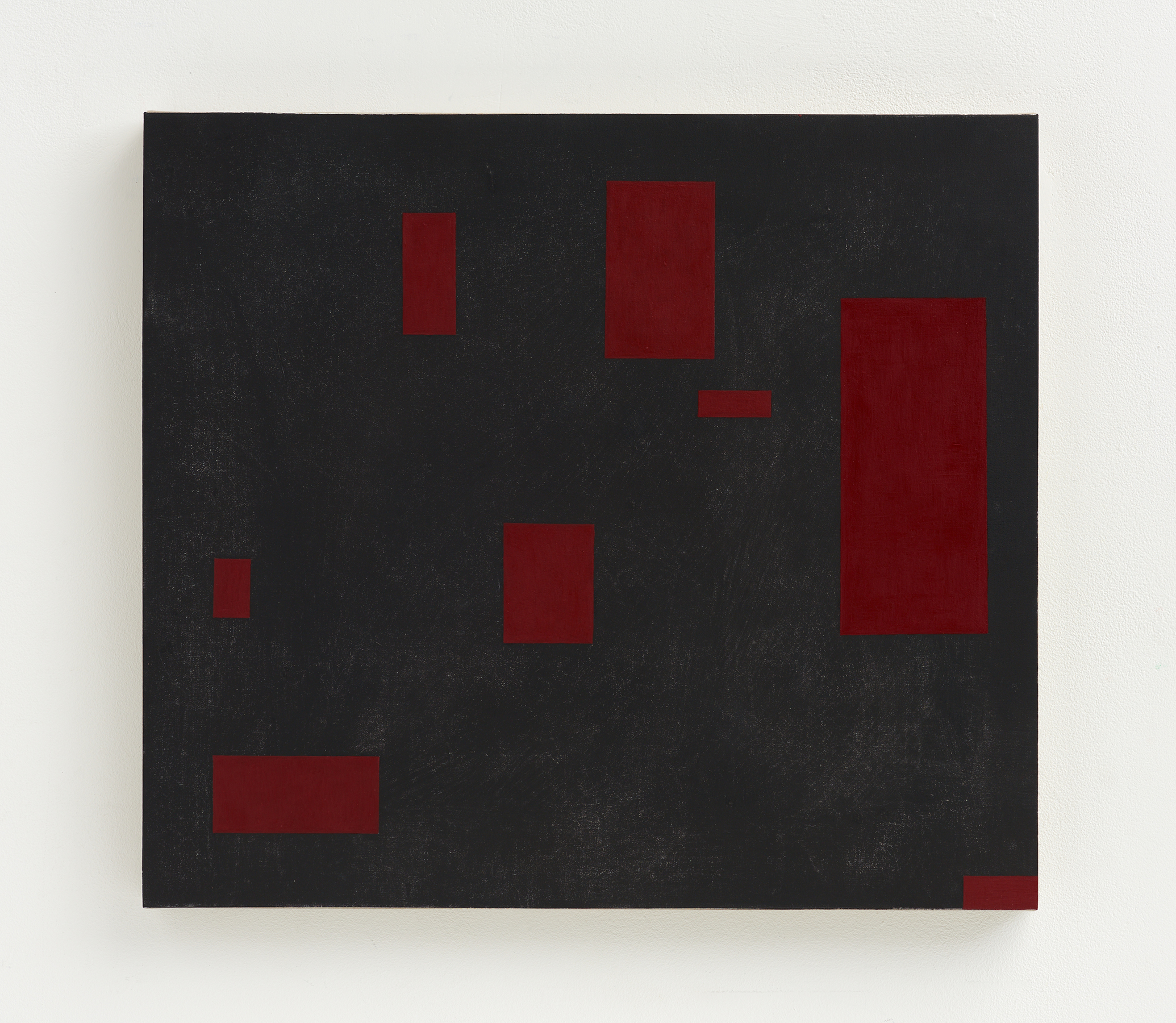

Alison Turnbull's expansive painting series 'eXtreme Deep Field' derives from a composite astronomical image made using the Hubble Space Telescope, eXtreme Deep Field. For Turnbull the Hubble image, has a strong relationship with painting: "It’s a picture of time that is very densely constructed; if you looked out through a telescope you would never actually see this, and it moves photography far beyond the question of analogue or digital… Here the notion of the 'onement' of painting is set against the infinity of the image."

Emma McNally (b. 1969, Essex) lives and works in London. McNally studied Philosophy and Literature at the University of York before continuing her thinking visually through drawing. Recent group and solo exhibitions include: The Drawing Room, London, UK (2024); ‘Afterness’, Artangel / National Trust, Orford Ness, UK (2021); 20th Biennale of Sydney, AU (2016) and ‘The form of the Form’; Lisbon Architecture Triennale (2016); ‘Mirrorcity’, Hayward Gallery, London, UK (2015); ‘Seeing/Knowing’, Kenyon College of Liberal Arts, Ohio, US (2011).

Alison Turnbull, (b. 1956, Bogotá, Colombia) lives and works in London. Turnbull transforms readymade information – plans, diagrams, blueprints, charts – into abstract paintings. Selected solo and group exhibitions include Casas Riegner, Bogotá (2025); Inverleith House, Edinburgh (2022); Many Minute Attentions, co-curated by Alison Turnbull and John Stezaker, Large Glass (2021); Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (2021); Saicoro, Tokyo (2020); Matt’s Gallery, London (2018); Five Easy Pieces, Large Glass, London; (2017); Turner Contemporary, Margate (2016); De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill (2014); Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (2012).

Emma McNally

Alison Turnbull

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Exhibition Text

‘The Edge of Forever’, Dava Sobel, June 2025

Alison Turnbull

Enquiries

sales: Charlotte Schepke

info: Gabrielle Slack-Smith

Exhibition Text

‘The Edge of Forever’, Dava Sobel, June 2025